21st Century Civilization: Week 8 — Industry and Money

A comprehensive digest of the Week 8 discussion on Industry and Money from the 21st Century Civilization curriculum, covering Chinese industrial policy, monetary systems, GDP methodology, and civilizational trajectories.

Table of Contents

Personal Note: EET + SGT Week 8 discussion notes/digest. It’s rather longish—the canonical URL has a ToC, formatted by Claude Code Opus 4.5 with reasonable input by myself. Considering meeting notes are by default mediocre as rather pure LLM input these days, I just wanted it to be a bit loquacious. I did formalize the language, removed the contributors’ names to preserve privacy; some wordings might sound a bit too diplomatic/hygienic but I think they are OK. I directly published it on Substack since I think it’s good to signal such discussions to network clusters and I just don’t like confining such notes to mere docs where debates/discussion do not take hold properly.

It’s formatted to be easily queryable by the average LLM model so feel free to feed it to your own agents—I wonder how it would feel like if we could feed as many agents into a sandbox that is the mirror life of this discussion group by emulating each contributor here and network via their own orchestration.

In fact I have an idea around such an approach with contextual event contract market deduction tooling—I presume this is very relatable to this week’s core, that is industry & money, if money-ness is still a thing.

Discussion Group Session

Host & Moderator: Gökhan Turhan

Time Zones: Singapore Time (SGT) & Eastern European Time (EET)

Curriculum Reference: 21st Century Civilization Week 8

Table of Contents (click to expand)

- Part I: Thematic Digest

- Part II: Thematic Discussion Summary

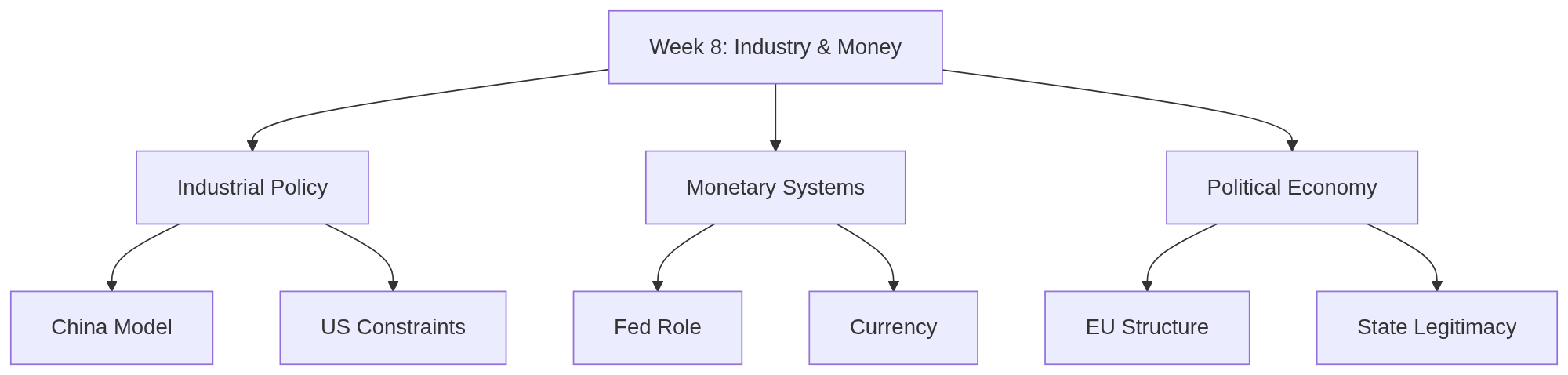

- Figure 7.1: Week 8 Themes Mind Map

- 8. GDP Methodology and Economic Measurement

- 9. Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy

- 10. China Industrial Policy and Overcapacity

- 11. American Infrastructure and Institutional Dynamics

- 12. Creative Destruction and Economic Dynamism

- 13. Monetary Systems and Currency

- 14. Tax Policy and Fiscal Dynamics

- 15. Cities, Currency, and the EU

- 16. Labor Markets and Comparative Perspectives

- 17. Legitimacy and Political Authority

- Part III: Higher-Level Abstract Questions

- 18. On the Epistemology of Economic Measurement

- 19. On the Topology of State Legitimacy

- 20. On the Dialectic Between Stability and Dynamism

- 21. On Currency as Governance Mechanism

- 22. On the Conditions of Industrial Greatness

- 23. On the Architecture of International Order

- 24. On the Relationship Between Economics and Politics

- 25. On Civilizational Trajectories

Part I: Thematic Digest

1. Overview

The Week 8 session examined the political economy of industrial development, monetary systems, and the geographic organization of economic activity. The curriculum’s four main readings provided the scaffolding for a wide-ranging discussion that moved fluidly between Chinese industrial policy, the epistemological limits of GDP measurement, the structural constraints on American and European economic dynamism, the critique of fiat currency, and the Jacobsian thesis on cities as the proper unit of economic analysis.

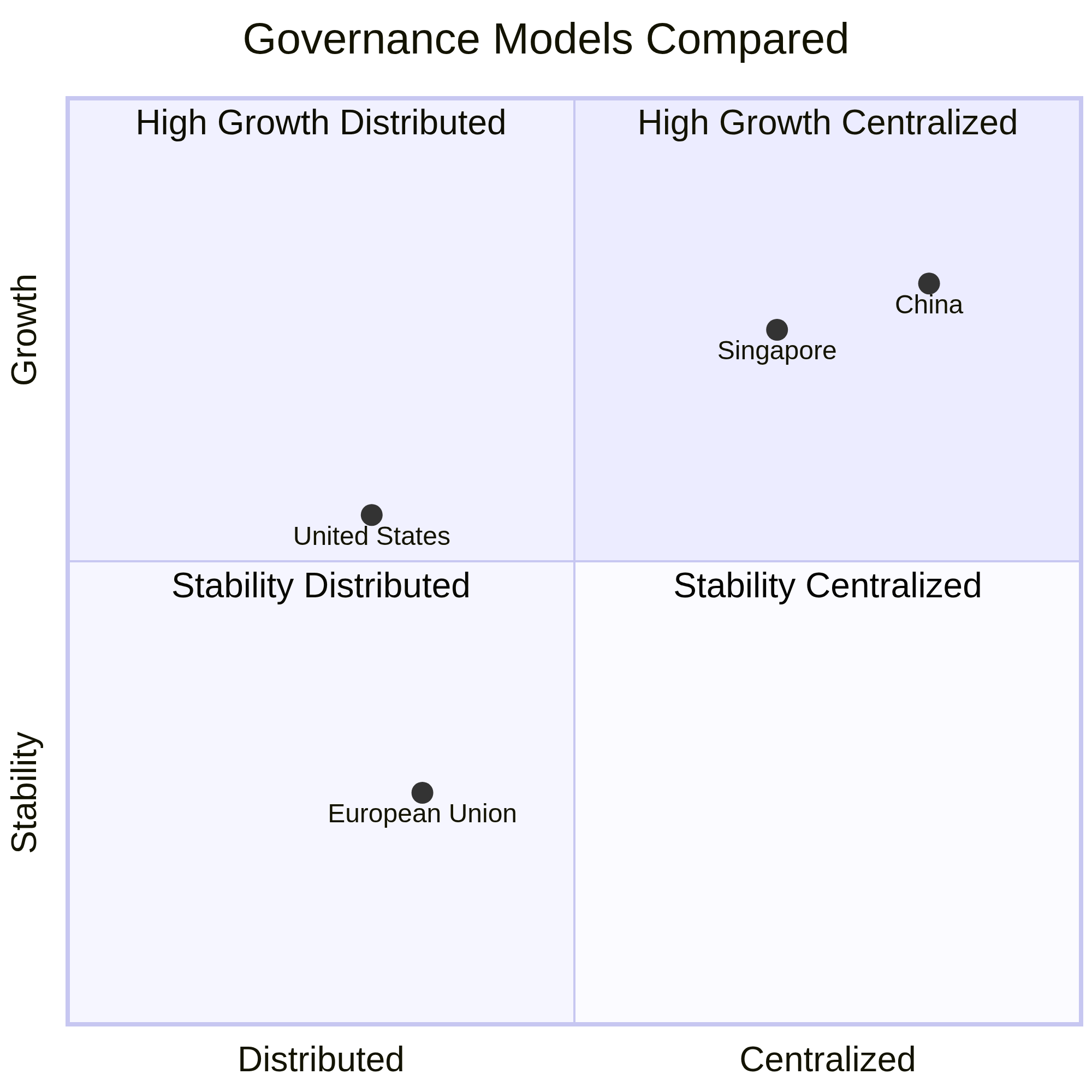

The discussion demonstrated particular engagement with the tension between state capacity and market dynamism—a tension that manifests differently across civilizational contexts. China’s centralized state capacity was contrasted with America’s pluralistic governance constraints and Europe’s preference for stability over growth.

Figure 1.1: Governance Models Quadrant

Comparative positioning of major economies on governance centralization and growth orientation axes.

2. The Real China Model

2.1 Curriculum Context

The first main reading examines Chinese industrial policy and the mechanisms by which state direction has produced manufacturing dominance. The article summarizes arguments from Dan Wang’s work on how China has achieved industrial scale through deliberate policy choices that Western liberal economies structurally cannot replicate.

2.2 Discussion Themes

A. State Intervention and Knowhow Transfer

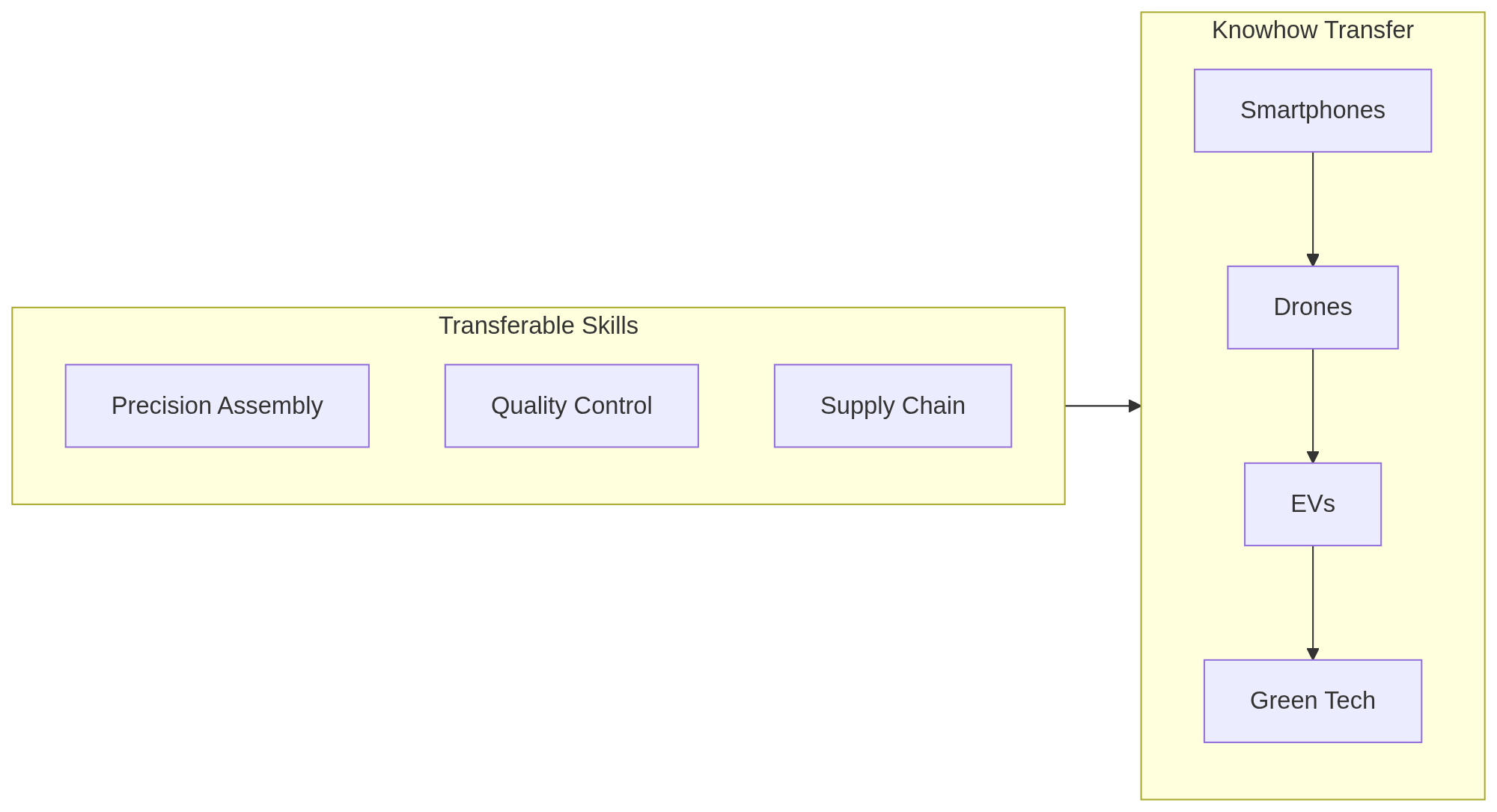

The group engaged extensively with Dan Wang’s book Breakneck, exploring the central argument about transferable technical knowhow embedded in China’s manufacturing workforce. The discussion noted that workers in manufacturing hubs like Shenzhen develop skills that transfer across industries—from smartphone assembly to drone manufacturing to electric vehicles. This creates a self-reinforcing ecosystem of industrial capability.

Figure 2.1: Knowhow Transfer Ecosystem

Flow of transferable manufacturing skills across industries in Chinese industrial hubs.

By contrast, the American model’s focus on innovation and product discovery without maintaining domestic manufacturing capacity results in the gradual loss of this embedded workforce knowhow—a form of tacit knowledge that cannot be easily recovered once lost.

B. Centralized Policy Coordination

The discussion noted China’s ability to redirect entire economic sectors through unified policy coordination—exemplified by the pivot away from consumer tech companies toward heavy industry. This capacity for rapid sectoral reorientation differs from liberal democracies where property rights and legal processes distribute decision-making authority across multiple stakeholders.

C. Overcapacity and Trade Policy

The discussion examined the structural challenge of Chinese overcapacity. The observation was made that China has not fully developed an internal market sufficient to absorb its manufacturing output, leading to export-driven strategies. This creates complex dynamics for international trade policy, as different nations pursue varied approaches to engaging with Chinese manufacturing capacity. The group explored how multilateral coordination presents challenges when allied nations have divergent domestic economic interests.

D. Chinese Tax Structure

An underappreciated factor in Chinese growth was introduced: consumption-based taxation that does not penalize savings and investment. Unlike income-based tax systems that can discourage business expansion by taxing investment directly, consumption-based approaches place the tax burden on final consumption rather than capital formation. This structural difference may contribute to lower barriers for economic growth and industrial expansion.

E. Market Scale as Buffer

Drawing a parallel to 19th-century America, the discussion argued that large internal markets can absorb policy inefficiencies. Historical American tariff policy, while theoretically suboptimal according to economic textbooks, did not prevent prosperity because the large internal market provided sufficient scale for specialization and productivity gains. China’s similarly vast internal market may provide comparable resilience.

3. Industrial Greatness Requires Economic Depressions

3.1 Curriculum Context

The second reading advances the Schumpeterian argument that creative destruction—including the pain of economic downturns—is necessary for long-term industrial greatness. Protecting inefficient firms and workers from market discipline produces stagnation.

3.2 Discussion Themes

A. The Psychology of Creative Destruction

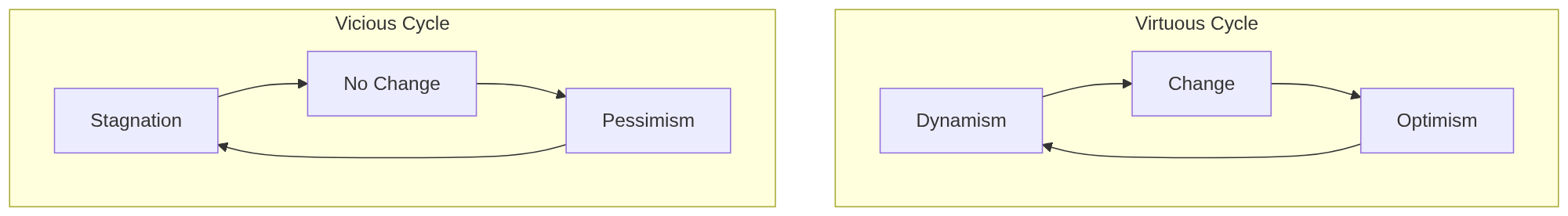

The group connected economic dynamism to psychological orientation. In rapidly developing economies, visible transformation—rice fields becoming high-rise districts within a decade—creates tangible evidence that change brings opportunity. This fosters optimism and willingness to adapt.

By contrast, in stagnant economies, the absence of visible dynamism encourages conservative orientations. When change appears unlikely to bring improvement, rational actors shift from “playing to win” to “trying not to lose”—prioritizing status preservation over risk-taking.

Figure 3.1: Virtuous and Vicious Economic Cycles

Self-reinforcing cycles of optimism/dynamism versus pessimism/stagnation.

B. The Trade-off Europe Has Made

The discussion articulated the implicit social contract in prosperous Western economies: a willingness to sacrifice growth for stability. Comprehensive safety nets guarantee relatively comfortable lives, but this comes at the cost of dynamism. Bailouts for failing companies, protections for inefficient sectors, and resistance to disruptive change all represent choices that prioritize stability over growth.

The observation was made that creative destruction is easy to endorse in the abstract but difficult to accept when it affects one’s own sector, job, or community. This asymmetry between theoretical assent and practical acceptance may explain why prosperous societies consistently choose stability.

C. American Institutional Constraints

The discussion cited analysis of why America faces challenges replicating Chinese building capacity. The institutional structure—property rights protections, environmental review processes, litigation possibilities—creates multiple points where projects can be delayed or blocked. The contrast with high-speed rail development illustrated this: comprehensive national networks built in years elsewhere versus decades of delay and cost overruns for much smaller projects.

Changing these incentives requires not just policy reform but a shift in the underlying mentality that views building and development with suspicion.

D. Fertility as Economic Indicator

The demographic manifestation of economic pessimism was noted: declining fertility rates may reflect rational assessments that children’s futures will be worse than their parents’ present. This creates a feedback loop where pessimism reduces investment in the future, which validates the original pessimism.

4. The Debtor’s Revolt

4.1 Curriculum Context

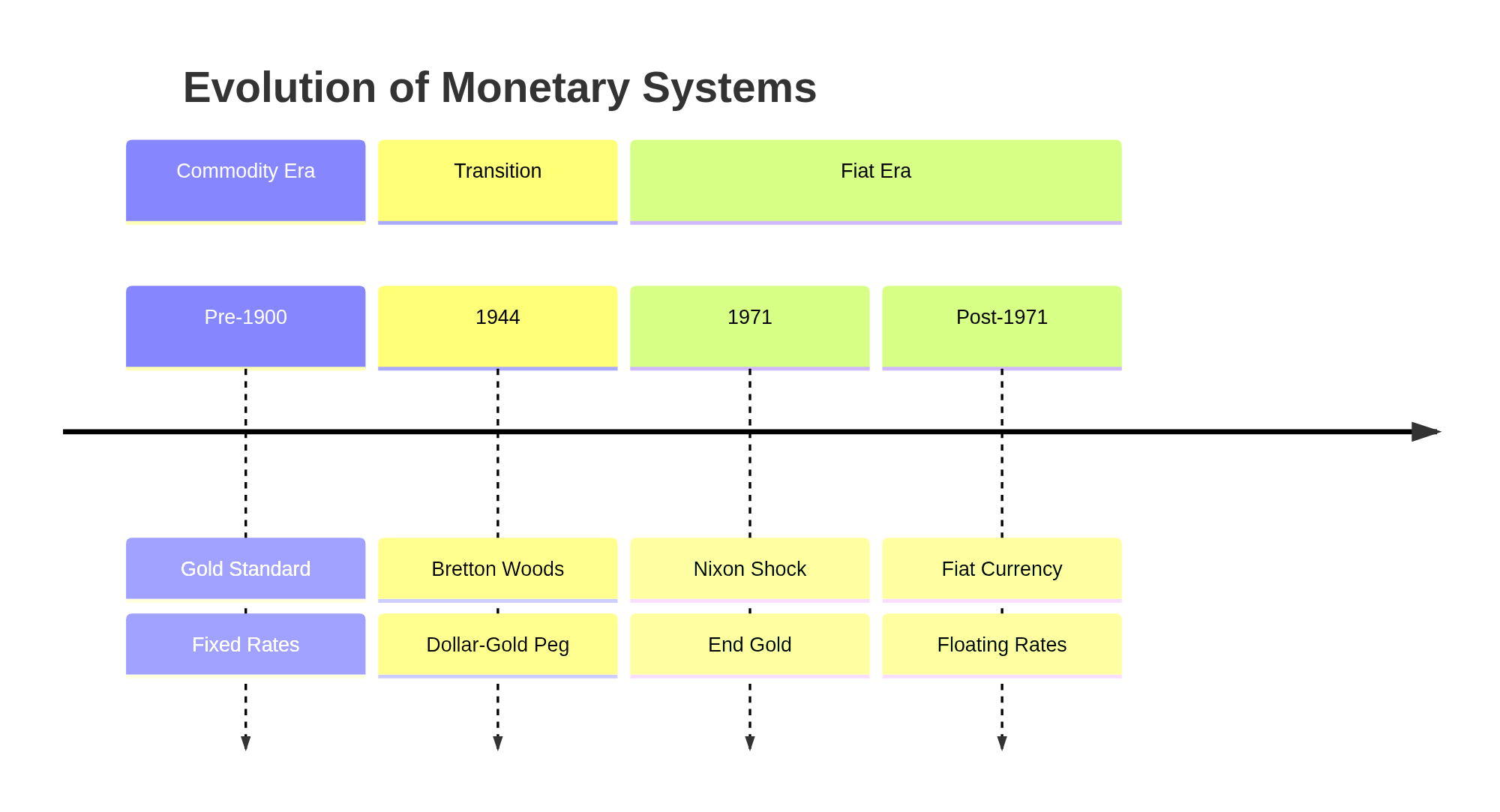

The third reading traces the historical shift from the gold standard to fiat currency and debt-based monetary systems, arguing that this transition has enabled state fiscal expansion and potential wealth destruction.

Figure 4.1: Evolution of Monetary Systems Timeline

Historical progression from commodity-backed currency to modern fiat systems.

4.2 Discussion Themes

A. Narrative Assessment

The group expressed mixed views on the article’s framing. While the historical narrative of increasing debt orientation makes sense, some participants noted it represents a particular school of economic thought. The observation was made that rigid standards like the gold standard can also constrain economic growth, and that the flexibility of fiat currency represents a double-edged sword rather than a pure negative.

B. The Double-Edged Sword of Fiat

States with fiat currency have greater capacity to finance activities, but historically have often employed this capacity suboptimally. The question of whether markets would allocate resources more efficiently than state-directed spending remains contested, but the track record suggests caution about expanded state financing capacity.

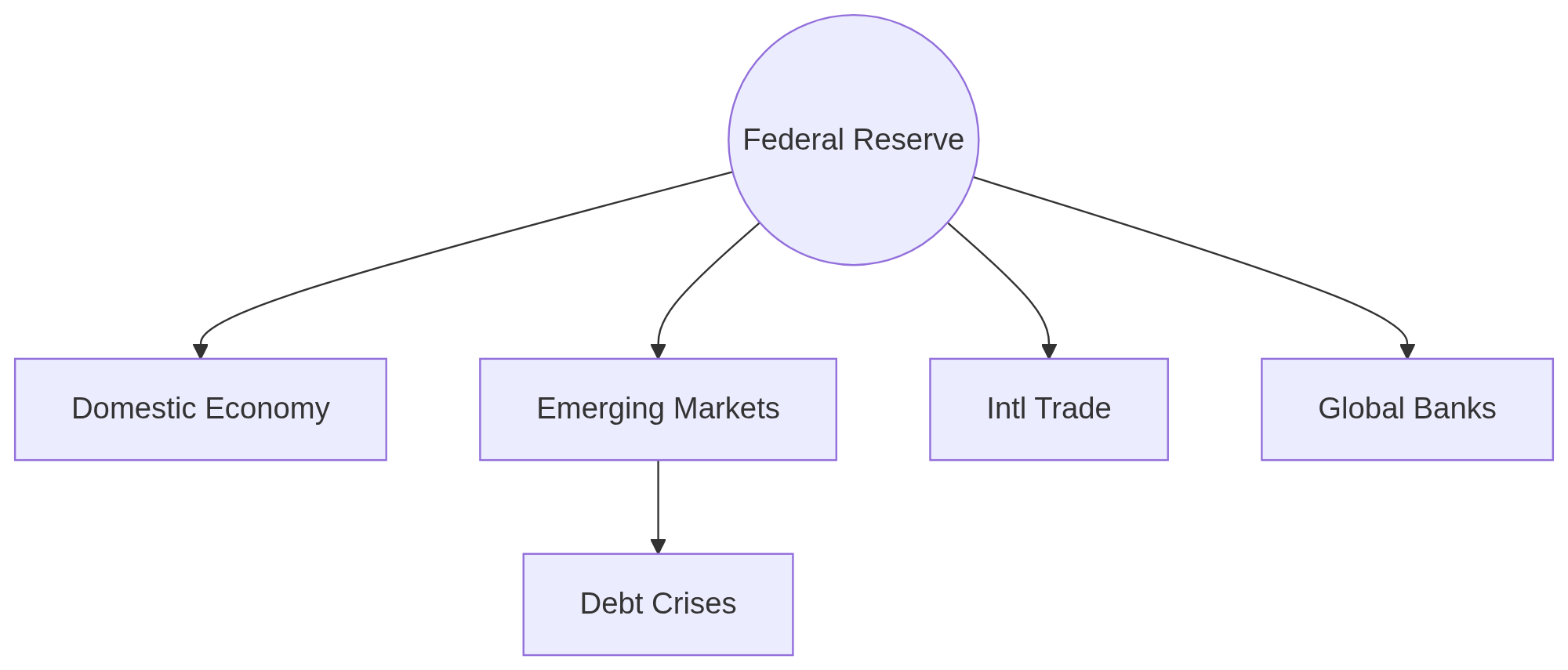

C. The Fed as World Central Bank

The discussion connected monetary policy to geopolitical influence. Because the dollar serves as the primary currency for international trade, Federal Reserve decisions have global implications. Rate increases can create debt servicing challenges for countries and businesses with dollar-denominated obligations, illustrating how monetary policy extends beyond domestic concerns.

Figure 4.2: Federal Reserve Global Influence

Hub-and-spoke model of Federal Reserve policy impact on global economic actors.

D. Monetary Policy and Executive Priorities

The group explored the ongoing discussion around Federal Reserve policy and executive branch perspectives, noting the complexity of balancing different stakeholder interests. Those with backgrounds in interest-rate-sensitive industries naturally favor lower rates, while financial institutions require sufficient rates for viability. Finding appropriate balance requires weighing multiple legitimate but competing interests.

5. Cities And The Wealth Of Nations

5.1 Curriculum Context

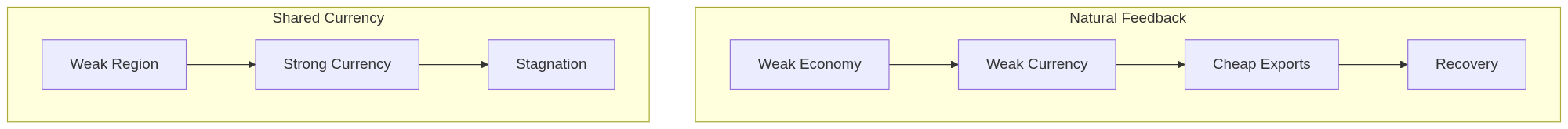

The fourth reading presents Jane Jacobs’ argument that cities, not nation-states, are the proper unit of economic analysis. Currency fluctuations naturally serve as feedback mechanisms for regional economic health, but this signal is destroyed when diverse regions share a single currency.

5.2 Discussion Themes

A. The City as Economic Unit

The group defended Jacobs’ underappreciated thesis. Without dynamic cities generating innovation and investment, nations become dependent on external sources for everything new. The city as the locus of economic activity may be more analytically useful than the nation-state, which often aggregates highly diverse regional economies.

B. Currency as Feedback Mechanism

The Jacobsian insight on currency was explained: weak economies naturally develop weak currencies, making imports expensive and exports cheap. This creates automatic pressure toward productive investment—only imports that genuinely increase productive capacity (like manufacturing equipment) make sense when currency is weak. Shared currencies eliminate this feedback mechanism.

Figure 5.1: Currency Feedback Mechanisms

Contrasting natural currency adjustment with shared currency distortion effects.

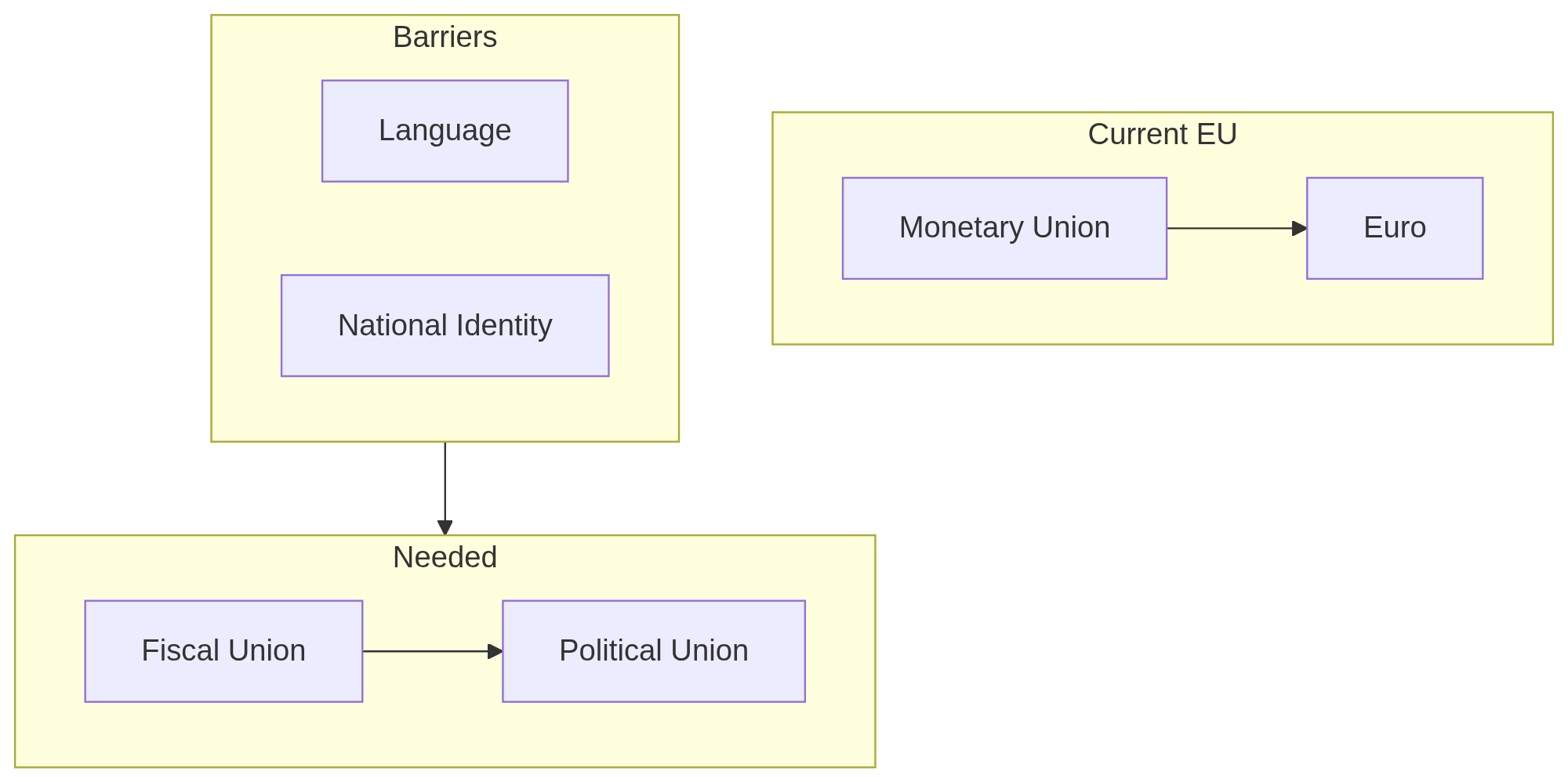

C. The Euro’s Distortive Effects

The observation was made that the euro represents different things for different economies. For stronger economies, it may be weaker than an independent currency would be; for weaker economies, it may be stronger. This creates structural imbalances: exports from stronger economies become artificially competitive while weaker economies lose the natural adjustment mechanism that would encourage development.

The discussion noted that even within single nations, significant regional variation exists. Northern and southern regions of the same country may have sufficiently different economic situations that a single currency serves neither optimally.

D. The EU’s Structural Contradictions

The group diagnosed the EU’s fragility: economic growth could paper over difficulties, but stagnation exposes underlying tensions. The EU comprises states that retain sovereignty, have never been truly unified, and maintain strong national identities. The language barrier alone prevents the free movement of people that would create genuine economic integration.

The distinction between monetary union and fiscal union was noted as crucial. Without fiscal union, member states cannot respond effectively to asymmetric economic shocks. But fiscal union would transform the EU from an international organization into a federal state—a transformation for which political will may not exist.

Figure 5.2: EU Structural Integration Gap

Relationship between current EU structure, required integration levels, and barriers to further unification.

6. Supplementary Readings and Additional Themes

6.1 GDP Measurement Challenges

The group provided detailed analysis of GDP measurement challenges:

- Quality adjustments can create misleading impressions: if a processor becomes twice as fast, counting it as double the output may overstate actual economic benefit

- Value added can increase even when physical production declines, creating statistical artifacts that obscure real trends

- Imputed rent (counting hypothetical rent for owner-occupied housing) is calculated differently across countries

- Government spending is counted as production regardless of value created—filling holes and unfilling them would register as positive GDP

- Black economy estimates vary widely and add significant uncertainty to cross-national comparisons

These methodological issues suggest caution when interpreting GDP figures, particularly for cross-national comparisons.

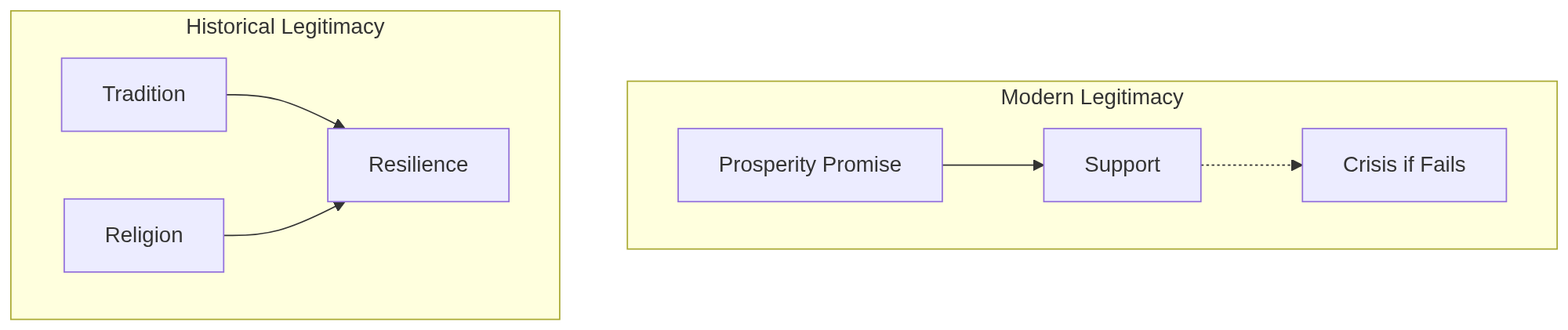

6.2 Crisis of Authority

The group reflected on sources of political legitimacy. Modern states largely base legitimacy on material prosperity—the promise that citizens will be better off. But material prosperity cannot increase indefinitely; when hard times come, materially-based legitimacy becomes fragile.

Historical regimes like the Habsburgs and Romanovs maintained power for centuries without promising material prosperity. Non-material sources of legitimacy—tradition, religious sanction, dynastic continuity—provided resilience that material legitimacy lacks. When a materially-legitimate regime loses a war or faces economic crisis, it may have no foundation to fall back on.

Figure 6.1: Modern vs Historical Legitimacy

Contrasting fragile material-based legitimacy with resilient non-material foundations.

6.3 Hayek and Distributed Knowledge

The group noted this supplementary reading deserved consideration as a main reading, as it addresses fundamental questions about distributed knowledge and economic coordination that underlie many of the week’s themes.

6.4 Tax Policy Dynamics

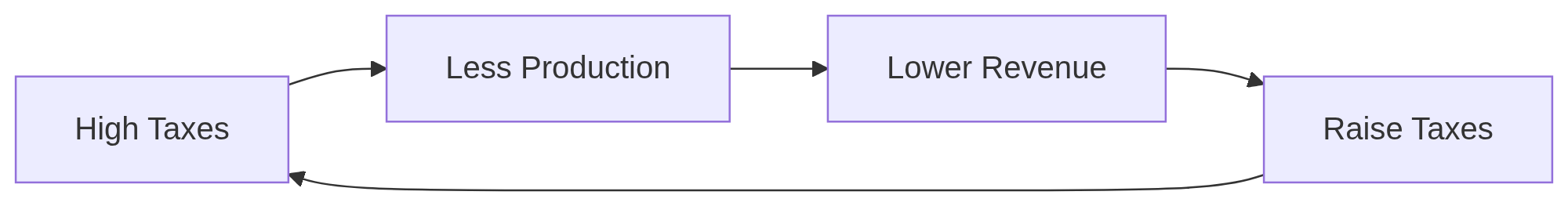

The discussion touched on contemporary tax policy debates as examples of late-stage fiscal dynamics. When tax burdens reach levels where additional income yields diminishing returns after taxation, rational actors may redirect effort from productive work toward securing state benefits. This can create self-reinforcing dynamics where increasing taxation reduces the tax base, prompting further increases.

Figure 6.2: Fiscal Pressure Spiral

Self-reinforcing dynamics of taxation, production incentives, and behavioral responses.

Historical parallels were noted: populations under excessive tax burdens have historically sometimes welcomed changes in governance that promised fiscal relief.

6.5 Labor Cost Behavioral Effects

The difficulty of empirically determining optimal tax rates was discussed. While the theoretical relationship between tax rates and revenue exists, identifying the optimal point remains elusive.

Behavioral responses to high tax and labor cost environments were noted: in high-cost environments, individuals often perform tasks themselves that they would hire specialists for in lower-cost environments. This represents an economic inefficiency—professionals doing amateur electrical work or construction—but a rational individual response to cost structures.

7. Next Session Preview

The group prepared for Week 9 (“Sociopolitics”), with participants selecting readings on elite coordination, institutional dynamics, and epistemological foundations for healthy decision-making.

Part II: Thematic Discussion Summary

Figure 7.1: Week 8 Themes Mind Map

Central themes and sub-topics covered in the Week 8 discussion on Industry and Money.

8. GDP Methodology and Economic Measurement

The discussion opened with analysis of how GDP statistics can obscure rather than illuminate economic reality. Participants explored several methodological concerns:

Quality adjustments in GDP calculation can create misleading impressions of productivity. When technological improvements are counted as output increases, statistical measures may suggest economic health that doesn’t correspond to tangible production. The group noted examples where reported value added increased dramatically while physical production actually declined.

Cross-national comparability was questioned. Different countries employ different conventions for imputed rent, black economy estimates, and government spending treatment. If methodologies differ, comparing GDP figures across nations becomes problematic—like comparing measurements in different units.

Government spending receives special treatment in GDP accounting: it’s counted based on cost rather than value produced. Unlike market transactions where price reflects willingness to pay, government expenditure registers as production regardless of whether it creates value. This asymmetry can make unproductive government activity appear economically positive.

The group concluded that while GDP remains useful, significant uncertainty should accompany any interpretation, particularly for cross-national comparisons or assessments of industrial health.

9. Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy

The discussion examined the relationship between monetary policy and various stakeholder interests. Participants noted that the Federal Reserve functions in some sense as a world central bank, given the dollar’s role in international trade.

Different economic actors have legitimately different interest rate preferences based on their situations. Those in interest-rate-sensitive industries naturally prefer lower rates, while financial institutions require sufficient rates for viability. Finding appropriate balance requires weighing these competing interests.

The global implications of Fed policy were discussed: rate changes affect not just domestic actors but any entity with dollar-denominated obligations. Historical examples of emerging market debt crises triggered by Fed rate increases illustrated this dynamic.

10. China Industrial Policy and Overcapacity

The group extensively discussed Chinese industrial development, drawing on the curriculum reading and Dan Wang’s Breakneck.

Knowhow transfer emerged as a central theme. China’s manufacturing workforce has developed transferable skills that move across industries—workers who assembled smartphones can transition to drone manufacturing or electric vehicle production. This creates compounding advantages as the knowledge base deepens.

State coordination capacity enables rapid sectoral pivots that distributed decision-making systems cannot easily replicate. The ability to redirect resources toward prioritized industries—even at the cost of previously favored sectors—represents a different governance model with different capabilities and trade-offs.

Tax structure was identified as an underappreciated factor. Consumption-based taxation that doesn’t penalize investment may contribute to growth dynamics independent of explicit industrial policy.

Market scale provides resilience. Large internal markets can sustain specialization and absorb policy inefficiencies that would cripple smaller economies. Both 19th-century America and contemporary China illustrate this dynamic.

Overcapacity challenges were discussed as a structural issue requiring international coordination. When domestic markets cannot absorb production capacity, export-driven strategies create complex dynamics for trading partners with their own domestic interests to balance.

11. American Infrastructure and Institutional Dynamics

The discussion examined why large-scale building projects face greater challenges in the American system than in more centralized governance structures.

Institutional structure distributes decision-making authority across multiple stakeholders, each with potential veto power. Property rights, environmental review, litigation possibilities, and regulatory approval processes create numerous points where projects can be delayed or stopped. While each protection serves legitimate purposes, their cumulative effect can make large projects extremely difficult.

The high-speed rail comparison illustrated the contrast: comprehensive national rail networks built in years elsewhere versus decades of delay and billions spent for minimal progress in the United States.

Mentality was identified as an underlying factor. Beyond specific regulations, a general orientation that views building and development with suspicion creates resistance that policy reform alone may not overcome.

The group discussed whether these represent inherent trade-offs of pluralistic systems or reformable pathologies that could be addressed without abandoning core liberal commitments.

12. Creative Destruction and Economic Dynamism

The discussion explored the Schumpeterian thesis that economic progress requires the pain of creative destruction.

Psychological orientation connects to economic dynamism. Visible, rapid change creates evidence that adaptation brings opportunity, fostering optimism and risk-taking. Stagnation creates the opposite dynamic: when change seems unlikely to bring improvement, conservative status-preservation becomes rational.

The European trade-off was articulated: comprehensive safety nets and resistance to disruptive change represent a choice to prioritize stability over growth. This may be a legitimate preference, but it comes with costs that compound over time.

Fertility decline may reflect rational pessimism about future prospects. When populations implicitly judge that children’s futures will be worse than their own present, reduced family formation follows logically.

The group noted the asymmetry between theoretical acceptance of creative destruction and practical resistance when one’s own sector or community faces disruption.

13. Monetary Systems and Currency

The discussion examined the historical shift from commodity-backed to fiat currency and its implications.

The narrative of increasing debt orientation was acknowledged, though some participants noted this represents one school of economic thought. Rigid standards can also constrain beneficial economic activity, making the flexibility of fiat currency a double-edged sword rather than a pure negative.

State financing capacity increases with fiat currency, but historical evidence suggests this capacity is often employed suboptimally. Whether markets would allocate resources more efficiently remains contested.

Interest rate balance requires weighing competing legitimate interests: some actors benefit from lower rates, others from higher rates. Finding appropriate balance is genuinely difficult, not simply a matter of identifying the “correct” rate.

14. Tax Policy and Fiscal Dynamics

The discussion touched on contemporary tax policy debates and historical parallels.

Marginal incentives matter: when additional income yields diminishing returns after taxation, rational actors may redirect effort from productive work toward securing state benefits or avoiding taxation. This can create self-reinforcing dynamics.

Historical parallels were noted: excessive taxation has historically sometimes led populations to welcome governance changes that promised fiscal relief. This suggests upper bounds on sustainable extraction.

Behavioral responses to high labor costs were discussed: in high-cost environments, individuals perform tasks themselves that specialists would handle in lower-cost environments. While individually rational, this represents economic inefficiency at the aggregate level.

Optimal taxation remains elusive. While theoretical relationships exist between tax rates and various outcomes, empirically identifying optimal points has proven difficult.

15. Cities, Currency, and the EU

The discussion engaged extensively with the Jacobsian thesis about cities as economic units and its implications for monetary union.

Cities as fundamental units may be more analytically useful than nation-states, which often aggregate diverse regional economies. Without dynamic cities, nations become dependent on external sources for innovation and investment.

Currency as feedback mechanism was explained: weak economies naturally develop weak currencies, creating automatic pressure toward productive investment. Shared currencies eliminate this feedback, potentially trapping weaker regions in stagnation.

The euro’s effects differ by member economy. For some, the shared currency may be weaker than an independent currency would be; for others, stronger. This creates structural imbalances that compound over time, with economic activity gravitating toward already-strong regions.

EU structural challenges were diagnosed. Monetary union without fiscal union limits response capacity to asymmetric shocks. But fiscal union would transform the EU into something like a federal state—a transformation that may exceed existing political will. Language barriers alone prevent the labor mobility that would create genuine economic integration.

Growth as solvent was noted: economic growth could paper over many difficulties, but stagnation exposes underlying tensions in structures that lack deep cohesion.

16. Labor Markets and Comparative Perspectives

The discussion included comparative perspectives on labor markets and household economics across different national contexts.

In high-labor-cost environments, households commonly perform tasks that would be outsourced in lower-cost environments. While this represents individual adaptation to cost structures, it also represents aggregate inefficiency: professionals spending time on amateur home repairs rather than their areas of expertise.

The contrast between high-cost and low-cost labor markets illustrates how different cost structures create different patterns of specialization and different skill distributions across populations.

17. Legitimacy and Political Authority

The discussion concluded with reflections on the sources of political legitimacy.

Material legitimacy—the promise of prosperity—dominates modern political systems. But material prosperity cannot increase indefinitely, and when hard times come, materially-based legitimacy becomes fragile.

Non-material legitimacy provided historical regimes with resilience that modern states may lack. Dynasties that ruled for centuries did so without promising prosperity; when they faced setbacks, they had foundations beyond material success to draw upon.

The question for modern states: what happens when material legitimacy can no longer be sustained? Do alternative sources of legitimacy exist, or does material failure necessarily translate to political crisis?

Part III: Higher-Level Abstract Questions

The following questions synthesize the discussion into unified conceptual inquiries suitable for extended philosophical and political-economic reflection.

18. On the Epistemology of Economic Measurement

18.1 The Ontological Status of GDP

If GDP incorporates quality adjustments, imputed values, and estimated informal economic activity—each involving contestable methodological choices—to what extent does it constitute a measurement of economic reality versus a construction that shapes what we perceive as economic reality? Does the act of measuring economic activity through GDP create the very categories through which we understand prosperity and decline?

18.2 The Incommensurability of National Accounts

Given that different nations employ different accounting conventions (imputed rent, informal economy multipliers, government spending treatment), can cross-national GDP comparisons yield meaningful conclusions about relative economic health? Or do such comparisons constitute a category error—like comparing lengths measured in different, non-convertible units?

18.3 The Hermeneutics of Economic Statistics

When statistical methodologies systematically obscure industrial decline, should we interpret this as innocent technical limitation, institutional self-deception, or deliberate political mystification? What is the relationship between economic measurement and the interests served by particular representations of economic reality?

19. On the Topology of State Legitimacy

19.1 The Fragility of Material Legitimacy

If modern democratic states derive their legitimacy primarily from delivering economic prosperity, what happens when prosperity becomes structurally impossible to sustain? Does material legitimacy contain within itself the seeds of its own destruction—a promissory note that must eventually come due?

19.2 The Durability of Non-Material Legitimacy

The Habsburgs and Romanovs maintained power for centuries without promising material prosperity. What were the non-material sources of their legitimacy, and can such sources be reconstructed in modernity? Or has the disenchantment of the world permanently foreclosed pre-modern modes of political authority?

19.3 The Threshold of Extraction

If populations under excessive tax burdens have historically welcomed governance changes that promised fiscal relief, does this suggest an upper bound on extractive capacity beyond which legitimacy simply collapses? Is there a taxation threshold at which governance change becomes welcomed rather than resisted?

20. On the Dialectic Between Stability and Dynamism

20.1 The Trade-off of Creative Destruction

Schumpeterian creative destruction promises long-term prosperity through short-term pain. But if populations consistently choose stability over growth—preferring “not to lose” over “playing to win”—is this irrational, or does it reflect a legitimate preference that economic theory systematically undervalues?

20.2 The Phenomenology of Optimism

Workers witnessing rapid transformation cannot pretend change doesn’t exist; those inhabiting stagnant economies naturally become conservative. If economic dynamism produces optimism and optimism enables dynamism, while stagnation produces pessimism and pessimism entrenches stagnation, are these self-reinforcing cycles escapable through policy, or do they constitute civilizational fates?

20.3 Fertility as Economic Indicator

Declining fertility in stagnant economies may reflect rational pessimism about children’s futures. If so, does demographic decline represent a verdict passed by populations on their own civilizational trajectory? Is low fertility a symptom of decline, or decline itself?

21. On Currency as Governance Mechanism

21.1 The Jacobsian Insight

If weak currencies naturally push weak economies toward development (making imports expensive and exports cheap), while shared currencies eliminate this feedback mechanism, does monetary union constitute a form of governance that systematically transfers wealth from periphery to center while preventing peripheral recovery?

21.2 The Euro as Experiment

The euro may be simultaneously weaker than optimal for some economies and stronger than optimal for others, producing structural imbalances that compound over time. Does this demonstrate the impossibility of monetary union without fiscal union? Or does it demonstrate the impossibility of fiscal union without political union? And if political union is impossible given European linguistic and national diversity, is the euro a category error—an attempt to unify what cannot be unified?

21.3 The City-State as Political Form

If cities are the natural unit of economic analysis (as Jacobs argues), and if currency should ideally track regional economic health, does this imply that the nation-state is an economically irrational political form? Would a world of city-states with independent currencies be more economically efficient, even if politically fragmented?

22. On the Conditions of Industrial Greatness

22.1 The Knowhow Thesis

If manufacturing knowhow is embedded in workers and transferable across industries, and if this knowhow is lost when manufacturing is offshored, does the “innovation economy” model represent a civilizational choice to trade irreplaceable tacit knowledge for abstract intellectual property? Can this trade be reversed?

22.2 The Pluralistic Governance Challenge

If liberal democracies face structural challenges in executing large-scale building projects due to distributed decision-making authority (property rights, environmental review, litigation), while centralized states can build high-speed rail in five years, does this represent a permanent trade-off of pluralistic systems, or a configuration that can be reformed without abandoning core liberal commitments?

22.3 The Tax Structure as Industrial Policy

If consumption-based taxation (which does not penalize savings and investment) constitutes a structural advantage for industrial development, while income-based taxation discourages capital formation, does the Western tax structure represent an implicit choice against industrialization? Is tax reform a prerequisite for reindustrialization?

23. On the Architecture of International Order

23.1 The Fed as World Central Bank

If Federal Reserve policy creates challenges for entities with dollar-denominated obligations when rates change, does this constitute an exercise of influence through monetary means? Is dollar hegemony a form of governance that operates outside traditional accountability structures?

23.2 The Limits of Centralization

If centralizing institutions face increasing difficulty achieving consensus, and if decentralized alternatives gain appeal, what political forms might emerge to replace current international arrangements? Does the future belong to regional blocs, nation-states, city-states, or something not yet imagined?

23.3 The Coordination Challenge

If addressing global economic imbalances benefits from coordinated multilateral action, what are the structural challenges to achieving such coordination when different nations have divergent domestic economic interests? How do democratic systems balance long-term strategic alignment with short-term constituent priorities?

24. On the Relationship Between Economics and Politics

24.1 The Laffer Curve as Political Problem

If the optimal tax rate cannot be empirically determined, but tax policy must nonetheless be set, does this mean that taxation is fundamentally a political rather than economic question—a matter of power and ideology rather than efficiency?

24.2 The DIY Economy as Symptom

When individuals in high-cost environments perform tasks that specialists would handle in lower-cost environments, what does this reveal about the relationship between labor costs, tax burdens, and the allocation of human capital? Is the developed world’s DIY culture an inefficiency that developing economies will eventually adopt, or a pattern they can avoid?

24.3 The Lobbying Equilibrium

If high marginal tax rates make securing state benefits more rational than productive work, does this imply that redistributive taxation creates its own constituency—a class whose interests lie in maintaining and expanding redistribution rather than production?

25. On Civilizational Trajectories

25.1 The Historical Parallel

If fiscal dynamics in some jurisdictions parallel historical patterns of extractive spirals, what does this suggest about the lifecycle of prosperous polities? Is fiscal pressure an inevitable late-stage phenomenon, or a policy choice that can be reversed?

25.2 The European Question

Europe has chosen stability over growth, safety nets over dynamism, preservation over building. If this choice proves sustainable, it represents a civilizational alternative to both American dynamism and Chinese state capacity. If it proves unsustainable, it represents a slow-motion civilizational transformation. Which is it?

25.3 The Hayekian Foundation

If distributed knowledge and price signals are fundamental to economic coordination, what does this imply about the limits of centralized direction? Is the Hayekian framework vindicated by certain successes, challenged by others, or orthogonal to the question entirely?

This digest was prepared from a discussion of the 21st Century Civilization Week 8 curriculum held on 18 January 2026. The curriculum materials are available at 21civ.com.